Most of us genuinely want to do good. We see ourselves as caring, kind, informed, thoughtful and reasonable people. But good intentions alone do not prevent harm. In fact, without realizing it, we can participate in systems that cause harm even when we are trying to help.

We tend to think of harm as something one person does to another. But many of the most damaging forms of harm are not the result of individual cruelty. They are produced by systems, and protected by stories.

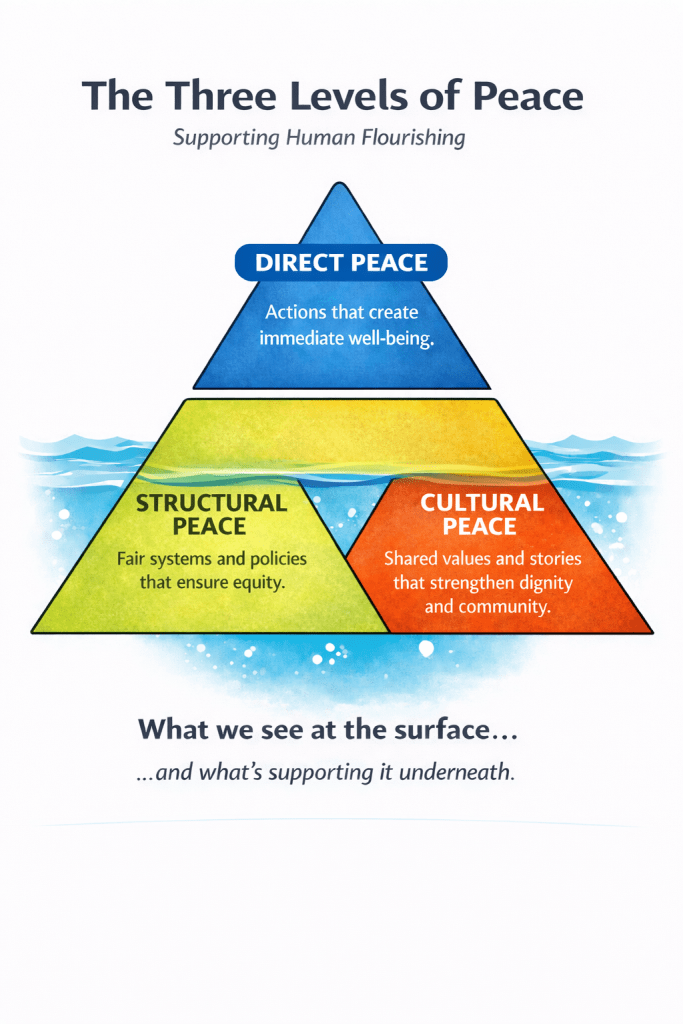

Peace scholar Johan Galtung gave us a simple way to understand this. He showed that harm and peace exist on three connected levels that shape our lives [1].

Direct harm: What we can see

This is the harm that happens in plain sight.

Physical violence, abuse, neglect, exploitation, discrimination, deprivation.

It is what people experience in their bodies and lives.

Direct harm is real and urgent, and it is usually the result of something deeper.

Structural harm: What makes it happen

This is harm built into how society is organized.

Unfair laws, economic systems, institutions, and power arrangements can quietly:

- limit people’s opportunities

- concentrate wealth and safety in some hands

- push risk and hardship onto others

No one person has to be cruel for structural harm to exist. The system does the harm.

Cultural harm: What makes it feel justified

This is the layer of stories, beliefs, stereotypes and assumptions that make unequal systems seem reasonable or deserved.

Cultural harm doesn’t usually sound violent. It sounds like common sense. But it is what protects harmful systems from being questioned.

How the three levels connect

Culture shapes what we believe is normal or fair.

Structure turns those beliefs into policies and systems.

Direct harm is what people experience as a result.

When people suffer, it is rarely random. It is usually the predictable outcome of stories and systems working together.

The Three Levels of Peace

Galtung named direct, structural, and cultural violence and coined the idea of positive versus negative peace. Later educators showed how peace can be understood in a similar way—what we experience, how systems support it, and how culture sustains it. The same framework also shows us something hopeful. If harm is produced through actions, systems, and stories, then peace must be built the same way.

Direct Peace

People are safe, fed, respected, and able to live with dignity.

Structural Peace

The systems people live inside are fair, inclusive, and designed to support human well being.

Cultural Peace

The stories a society tells affirm dignity, shared humanity, and mutual responsibility.

Why this framework matters

This way of thinking changes our approach.

“What kind of world are we participating in and helping to create?”

It reminds us that real peace is not built only by kindness between individuals, but by shaping the systems and stories that surround us. This framework can help us to see harm and healing not as accidents, but as patterns we can understand, question, and change.

Note

[1] Johan Galtung used the word violence to describe all forms of avoidable harm, not only physical force. In his framework, violence includes anything that prevents people from meeting their basic needs or reaching their full potential, whether through direct action, social structures, or cultural beliefs.

This is similar to how thinkers such as Marshall Rosenberg in “Nonviolent Communication” use the term violence to include not only physical injury but also systemic, emotional, and institutional harm that diminishes human life.

Because most people today hear the word violence and think only of physical attack, I use the word harm here because it is more likely to be understood in the broader sense Galtung intended: the full range of ways people are injured, limited, excluded, or made vulnerable by actions, systems, and stories.

Sources

Galtung, J. (1964). A structural theory of aggression. Journal of peace research, 1(2), 95-119.

Galtung, J. (1990). Cultural violence. Journal of peace research, 27(3), 291-305.

Galtung, J. (1964). Foreign policy opinion as a function of social position. Journal of peace research, 1(3-4), 206-230.

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of peace research, 6(3), 167-191.

Leshem, O. A., & Halperin, E. (2020). Lay theories of peace and their influence on policy preference during violent conflict. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(31), 18378-18384.

Moore, D. (2021). Methodological Assumptions and Analytical Framworks Regarding Religion. Harvard Divinity School/Religion Matters

Moore, D. (2015). “Two: Diminishing religious literacy: methodological assumptions and analytical frameworks for promoting the public understanding of religion”. In Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. Retrieved Jan 13, 2026, from https://doi.org/10.51952/9781447316671.ch002

Ragandang, P. I. C. (2024). In Honor of Johan Galtung, the Father of Peace Studies. Peace Review, 36(3), 491–498.

Short Video of Johan Galtung explaining his concepts of violene

The triangle of violence – a tool for context analysis

Leave a comment